This is the work of Dolly Joseph, and should not be used without express permission and compensation.

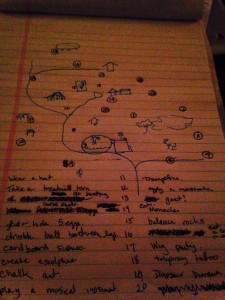

Before Engagement

Before heading into a community– for an internship, volunteering, seeking employment, whatever, it’s a good idea to situate yourself in relationship to the new project.

Feelings

Check in with yourself about how you are feeling– nervous, excited, timid, enthusiastic, apathetic… It’s okay to feel one or all of those feelings, and it’s also important to think about how the display of those feelings might be received by the community member(s) that you’ll be interacting with.

- What am I bringing to the community?

- How may I be received by this community? How do I feel about that?

- What will be challenging? What will be easy?

Skills

It’s also a good moment to take a skills inventory of yourself. What do you feel like you know how to do well? What could stand some improvement? What skills are you hoping to practice or develop with this opportunity.

- What am I bringing to the community?

- What relevant skills do I have? Is that enough? Where should I grow?

- What am I expecting to get out of this interaction?

- What am I expecting the community to get out of this interaction?

Information

It’s important to understand the context of the community that you will be engaging with. Do you have the needed information to engage in a positive manner? Have you gathered information from trusted, accurate sources?

- What am I bringing to the community?

- How have I educated myself about the community?

- What assumptions have I made? Are those fair?

- What expertise already exists in this community?

Resources

Resources can cut across these 3 categories– Resources can be related to access to information, time, money, emotional labor, etc. Often when we do community engagement in the form of volunteering we forget about the resources that are required to accommodate us as volunteers. It’s incredibly important to consider how resources are used when we engage with the community.

- What am I bringing to the community?

- What is the balance between what I will bring to this community (skills, open-mindedness, readiness to work, etc.) and what I will take (time, energy, etc.)

- What is the community [giving/sacrificing/risking] by hosting/partnering with me?

During Engagement

While you are within your community engagement, it’s important to consider how things seem to be going– both good and not-so-good. Remember, none of us are perfect. Often we get into the trap of thinking that there is no room for error. You will make mistakes, and then grow and learn from that practice. Reflecting and adjusting during your community engagement is a great way to improve your current and future experience.

- Am I effectively paying attention to direct and indirect communication?

- Am I engaging in effective, positive and/or productive interpersonal interactions?

- Am I using my skills in an appropriate, effective, and respectful way?

After Engagement

Even if your most recent community engagement was a “one off” commitment, you will have another experience in your future. It’s important to reflect on how things went so that you can be more effective next time.

- How do I know if my interaction was a positive experience for the community?

- How did my expectations differ from what happened?

- What should I do to have a positive and productive experience next time?

- What skills or resources should I access to improve my effectiveness?